Guns are a key part of being prepared. If there is a major disruption they can be an essential source of security and food. This leads to my 12th rule of prepping:

Rule 12. Slaves and the dead are unarmed

This sounds harsh and intentionally so. You don’t want to be unarmed two months into a grid collapse. Trust me about that.

Before moving on, I need to acknowlege and emphasize that guns are a necessary but not sufficient condition for successful prepping. This is why my next rule of prepping is:

Rule 13. You can’t eat or drink bullets

But more on that later. The focus here is Rule 12.

Guns are a topic that makes a lot of people uncomfortable. This is not wholly unreasonable. Guns are dangerous and people do a lot of stupid things with them (just like they do with, say, cars). But some of the fear, and maybe some of the stupidity, is probably driven by a lack of familiarity.

Guns certainly are not the only weapons you can , or should, use when prepping. But at the same time guns are indispensable. I have run into preppers with a great aversion to guns who argue that their substitute, such as a recurve bow, is just as effective. Well, the probability of someone with a recurve defeating someone with an AR-15, for instance, isn’t zero. But it is low. Very low. In the rock, paper, scissors game in a post-disruption world without the rule of law, guns break most other weapons and defensive schemes. You should not kid yourself about that.

In this and a long series of posts to come I am going to provide an introduction to guns. I write under the assumption that the reader knows nothing about them and build from there. If you know everything up to a certain point, jump in then. Alternatively, simplification can sometimes lead to potentially misleading statements (e.g. missing important exceptions to general truths). If you feel I have done this, please call me out and I will edit appropriately.

Let’s begin at the most basic departure point:

A gun is a device that uses a cartridge (pictured above, showing a shape often associated with “rifle’ cartridges) to deliver concentrated energy to a target via a bullet (1). The two major parts of a cartridge are the bullet (1) and the casing (2). Generally speaking, guns ignite the primer at the bottom of a casing, which then sets off a larger charge within the casing.

The bullet is the part that is shot out of the gun. The casing of the round being fired is immobilized in the chamber of the gun. This is a section of the barrel (on many guns it is technically an extension of the barrel, but let’s not worry about that) in which the round to be fired is placed ready to be fired. It is usually held in the chamber by the bolt of the gun.

The ignition of the primer (by the gun driving what is called a firing pin into the primer) and then of the charge by the primer causes gas expansion, the mounting pressure from which in turn causes the bullet to separate from the casing and accelerate down the barrel.

The energy involved in this is basically constrained within the narrow barrel between the bolt and the back of the bullet. That constrained energy feeds the acceleration of the bullet to its final velocity when it leaves the barrel. The bullet then travels beyond the muzzle of the gun.

Its trajectory thereafter reflects three basic forces. Atmospheric resistance causes it to slow, until other things being equal, it comes to a stop. Gravity causes the bullet path to fall relative to a straight line out of the barrel. Finally, atmospheric movement of air (i.e. wind) causes shifts in its trajectory as they act on the bullet. These forces operate on the bullet until it either hits something or comes to a rest somewhere.

That’s it, in essence.

To round out the anatomy of a cartridge, from the image above we have the neck (3), shoulder (4), rim (5) and base (6). The details and implications of these are not super important for now.

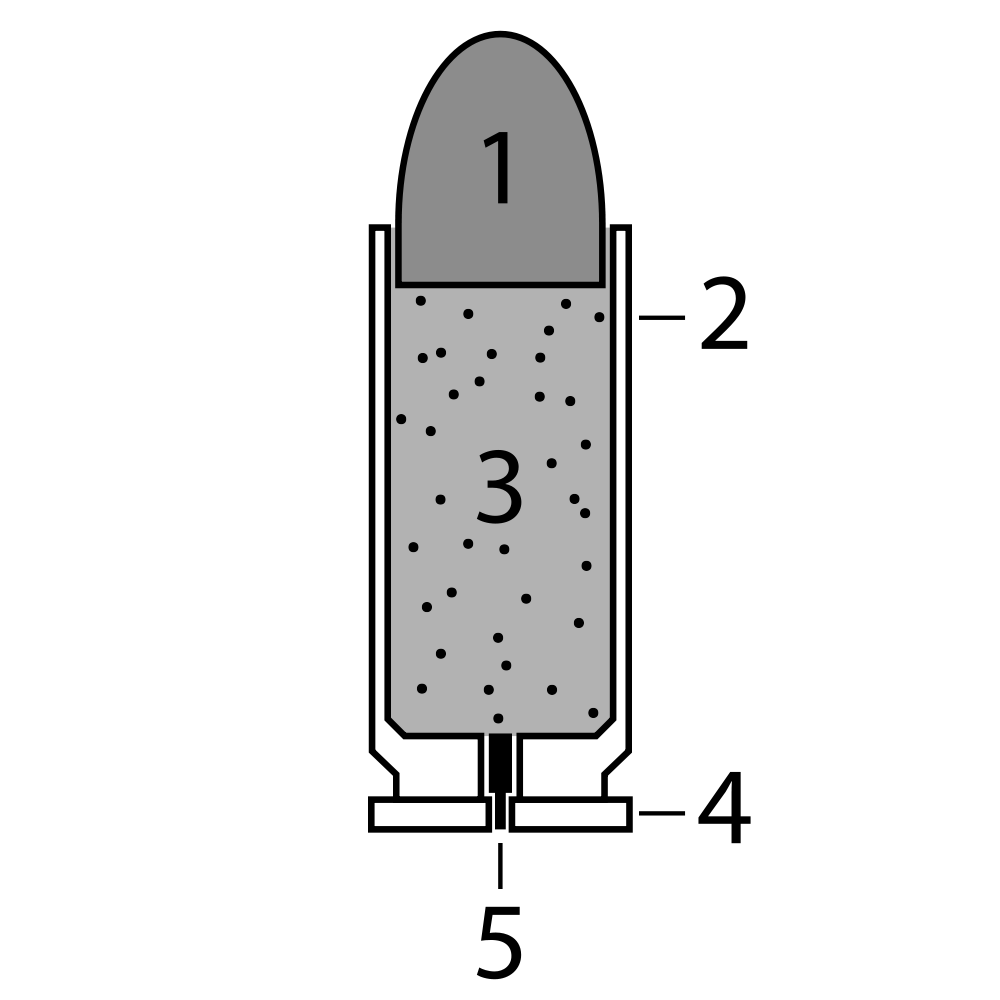

For those a little lost, below is another cross-sectional diagram of a cartridge, this time showing a profile more typical of a “pistol” cartridge (though to be sure, many rifles accept cartridges that look like this; for an example, Google “30 carbine” to see the cartridge for the M1 Carbine rifle from WWII) . Note the lack of a defined neck and shoulder. The bullet (1) is at the top of the cartridge and seated a bit in it. Striking the primer (5) ignites the charge (3), causing the bullet (1) to separate from the casing (2) and travel down the barrel.

From the operational basics of a gun flows two big realities:

- What bullets actually deliver is kinetic energy, which is the energy associated with an object due to its motion. And the kinetic energy of an object is its mass times (m) the square of its velocity (v):

e=m*v2

In terms of the energy delivered by a bullet, there are two big implications. First, there is a big payoff in terms of kinetic energy to higher bullet mass m, which is usually measured in grains (there are 7,000 grains in a pound). Second, there is an even more quickly growing payoff to the increasing velocity at which a round travels v (usually measured in feet per second). If someone threw a bullet at your chest, you would say “owww!”. If they shot it out of a gun at your chest you might be killed. The difference mainly reflects the implications of velocity for kinetic energy. - The damage a bullet does can depend on how the energy is delivered at the point of impact with the target. Some bullets designs concentrate energy (e.g. armor piercing bullets, which are in simple terms very hard and try to concentrate a huge amount of energy at a point to overcome great resistance) and some effectively act essentially to spread it (e.g. so-called “hollow point” rounds, which generally maximize damage to softer targets).

- The flight performance of a bullet once it leaves the barrel can also depend heavily on bullet design. For instance, some bullets experience a large amount of air resistance as captured in a low drag coefficient. This may or may not be a big deal depended on the intended mission of the bullet. For example, the AK-47 cartridge, the famous 7.62X39mm (also sometimes called the “7.62 Soviet”), has a generally low drag coefficient compared with many cartridges for similar guns. But the AK-47 was designed primarily with engagements out to 300 meters or so in mind, and from what I have seen that cartridge gets the job done to those distances

The discussion thus far has hinted at two types of guns: pistols and rifles. For legal purposes, there is actually a third category, called an “any other weapon” (often abbreviated to AOW). I don’t went to get into these too much in this post except to say that the only even quasi-clear defintions for these are legal, and due to rapdily mounting innovation around legal technicalities, even these legal distinctions are starting to blur for practical purposes.

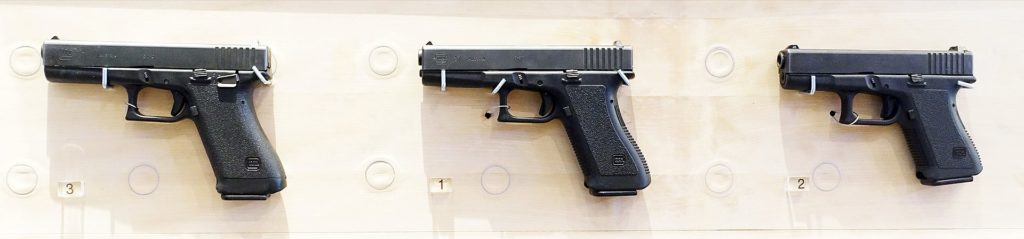

When most people hear “pistol” they think of this:

Or this:

But consider the image below taken from Reddit (from https://www.reddit.com/r/ar15/comments/ff459r/not_sure_which_one_i_like_shooting_more/ ):

The guns at the top and bottom are rifles, the one in the middle is a pistol. Confused? That makes you a sensible person. But don’t worry about this for now: they are all guns. We will return to this distinction, but pistol and rifle definitions for practical purposes are at this point very much a discussion in flux. We’ll discuss this further in a later post.

Before concluding I want to clean up a little more on the terminology. I referred to the “M1 Carbine” earlier. If you’ve seen Saving Private Ryan, Band of Brothers, etc, you have seen the M1 Carbine but for the uniniated here it is:

“Carbine” is one of those funny words you see bounced around in the gun world. Everyone familiar with guns generally understands what is meant in context when the term is invoked, but a precise definition that captures every application of the term is somewhat elusive. But the M1 Carbine is a pretty good example of the generally agreed on features of a carbine: it is a generally shorter, probably more maneuverable rifle and the term is sometimes also applied to rifles that chamber less powerful cartridges. For example, he is an M1 carbine next to the M1 Garand rifle:

And here is the M1 Carbine cartridge (.30 Carbine) next to the M1 Garand cardtridge (.30-06 Springfield, often referred to a “thirty aught six”):

Clearly, the M1 Carbine chambers a smaller cartridge and is a smaller gun, at least compared with the M1 Garand. Generally, in my experience carbine implies “short” more strongly than it does “less powerful cartridge” (for example, the M-16 and its carbine counterpart, the M4, generally still chamber the same cartridge, the 5.56X45mm). There are lots of other funny terms like carbine that are useful to know if a little fuzzy (e.g. some day we’ll talke about “recce”, which makes carbine look straightforward). For now it is important just to know that such words are abundant in the gun world, which evolved from a long and varied history, leading to a lot of sediment and confusion.

Finally, some slang. Bullets are sometimes called slugs, for example. Cartridges are sometimes called rounds. Confusingly, cartridges are sometimes referred to as bullets. And catridges, bullets, etc. are often referred to generically as “ammo” or “ammunition”. You’ll get used to it and you will learn how to process the almost unending malapropisms surrounding guns and shooting if you start with a good grounding in the fundamentals.