“We’re driving a U-Haul out to the Hamptons. Which means I’ll probably be the first to die”

So it turns out that covid-19 is messing with the Spring Break plans of our betters and instead they are doing what any sensible prepper would do in an emergency like this: bug out out to the Hamptons. To wit:

All kidding aside, bugging out is central to the plans of a lot of preppers. When the SHTF, they are going to hit the open road.

Now when I refer to “bugging out” for the purposes of what follows in this post I mean leaving your home in a major, society-wide SHTF social disruption. I am not referring to, say, driving to your brother’s house 200 miles away because your own is in the path of a Category 3 Hurricane or something like that. To me the better word for that is “evacuation” and the key distinction with “bugging out” is that if you evacuate in a timely, sensible fashion, your journey will be one aided by the fact that most of the support mechanisms of the modern world (e.g. gas stations) are still intact and your jorney will end in a place where they operate as well.

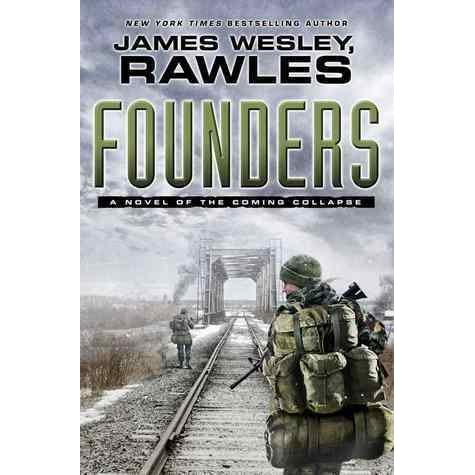

I cannot help but to think that roughly half of preppers who seriously contemplate bugging out so defined as an attractive option are stirred to do so by romantic disaster porn book covers. Exhibit A:

Most of the other half are probably motivated by images of the ultimate road trip from movies like Zombieland.

Here’s the most important thing to know about bugging out: it is generally a terrible idea that should be pursued only as a last and unavoidable resort.

First, let’s be honest: it would be physically grueling. You are most likely going to have to undertake a major part of your journey on foot and living out of a bag. In a real SHTF scenario the roads are likely to be challenging to say the least. Abandoned vehicles clogging the lanes. We know this is likely because it routinely happens in certified non-disasters. Consider the picture below that gave birth to a thousand internet memes, from an ordinary (and light) snowstorm in Raleigh, NC a few years ago. And most of you have vehicles that mostly confine you to roads (no, a Toyota Highlander is not a post-apocalyptic off road war machine).

So get used to the idea that bugging out will probably mean walking. Test yourself sometime by taking a 10 mile hike with a 50 pound pack and something heavy enough to simulate carrying a rifle. I bet you are in serious trouble by mile 4. You will also learn why blisters are such an obsession for those of us who recreationally put pack to back and ramble around the woods. If you would have to bug out in any kind of hilly or mountainous area I give to mile 2 before you are in trouble.

And here is an instrinsic problem: realistic physical conditioning will only go so far in getting you ready for this. The only real way to get ready for this is to hike constantly with a pack on, but that is a very time inefficient method of exercise. Even folks in pretty good shape will struggle with the practical physical realities of a long forced march with a lot of weight on their backs.

And if you are thinking about bugging out then you better think hard about gear. For instance, the dude on that book cover (“Founders”) above is wearing an “Alice” pack.

The Alice (as in All-Purpose Lightweight Individual Carrying Equipment) pack is a US military design that was adoptd in the early Seventies. Alice packs carry a lot of nostalgia weight. They were a foundational piece of kit for generations of US soldiers. And they are a comparatively very affordable pack (I bought one off of Amazon for evaluation maybe 7-8 years ago for $50 bucks or so). But here is the most important thing you need to know about Alice packs: they are not so good at carrying actual weight. With more than around 35-40 pounds in them they are a torture device.

You need a pack with a high speed frame that distributes the weight in a sustainable way (that is, away from your shoulders and toward the Iliac crest of your hips) that works with your body. Finding that pack is a financially and time expensive undertaking.

Bugging out is also a security and resources nightmare. You will likely be pushed into essentially unfamiliar operational environments for which you have little ability to anticipate risks or know where to look for things you might need. The locals know that new environment better than you. They know where to get food, water and resources better than you do. They know, frankly, where to ambush you.

Bugging out is also rooted in the idea that the grass is greener over there. While that is always possible, in many realistic disaster scenarios limited information flows will probably make it hard to determine whether this is really the case. And you are probably going to be betting a lot that conditions are better in your bug out destination.

Yes, these folks leaving for the Hamptons do not have the image of the book cover above in mind. But what makes them so sure the Hamptons isn’t actually ground zero for the next huge Covid-19 cluster? Would anyone have guessed the Orthodox Jewish community in New Rochelle would be the first huge cluster?

We are going to talk about bugging out but make no mistake about it: it is likely a desperate choice in most real SHTF scenarios. Your first line of defense should be bug in: stay where you are and try to ride out what is happening.

This is so important, and flies so strongly in the face of a type of prepper escapist fantasy, that it deserves a rule of its own:

Rule 23. Try to bug in